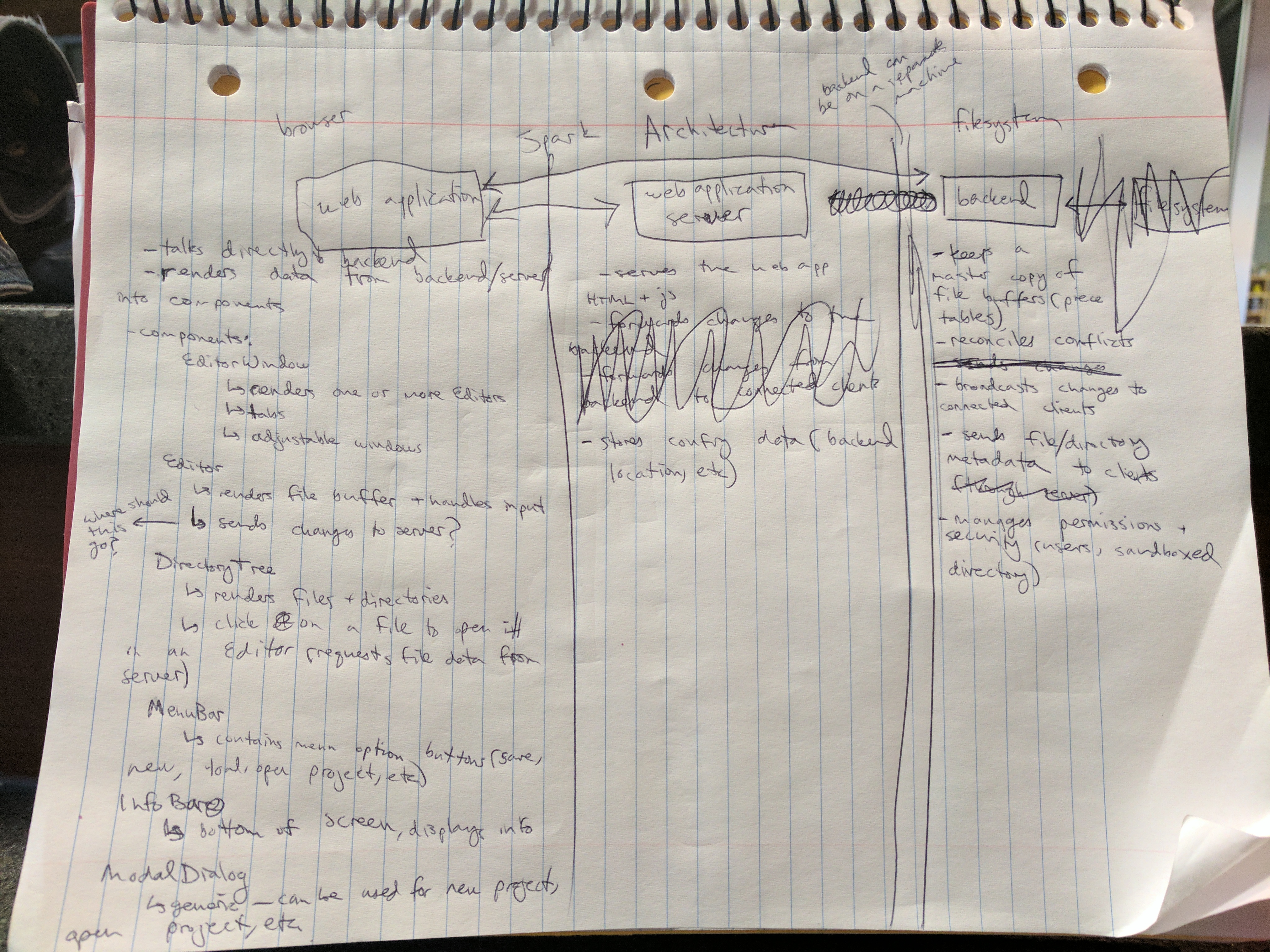

Spark Architecture

This is a brief summary of the proposed architecture for Spark. It's a first draft; expect many changes by the time I get to implementation.

The architecture can be divided into two discrete sections. The backend is a program that runs on the host that holds the files to be edited. The backend reads from and writes to those files, and communicates over WebSockets to connected clients. The client is a separate program; it serves the web application and communicates with the backend.

The Backend

For the MVP, the backend will be as minimal as possible. It will be a Node.js application with two primary roles: reading and writing to the file system, and communicating with the client applications. Without getting into too much detail, the program will use the fs module and the chokidar package to manipulate files. It will communicate with the clients in real-time using socket.io, a JavaScript WebSocket library. I've chosen to use WebSockets rather than HTTP for communication because WebSockets are bi-directional and real-time, eliminating the need for a polling strategy on the part of the client and hopefully giving users a more responsive experience. Although Node's event-driven, asynchronous nature will scale quite well, I will likely need to take care to ensure maximum scalability.

Each client will establish a single socket connection to the backend. The processes will send events over this connection - for example, reading the contents of a directory or making changes to file. The specific events will be figured out later, but will most likely be limited to file system I/O and some metadata (particularly, metadata required to sync up changes push by multiple clients). I anticipate that handling conflicts between clients will be the trickiest part of writing the backend.

The backend will also need to handle security and permissions. Broadly, the sysadmin of the backend machine will be able to define project directories. The backend will have some sort of user system (maybe tying in with the OS users?), and the sysadmin will be able to define what users have access to what projects. Projects will live in a central directory (~/.local/spark), and will be sandboxed, so users with permission to a project will be able to create files and directories in that project only.

As a stretch goal, I would like to implement an admin web interface for the backend. This would give sysadmins a GUI from which to add/edit/remove users, create or delete projects, change permissions, etc.

Eventually, it would be good to have an additional piece of software that lets the backend communicate with developers' machines directly. This would enable, for instance, developers to use Spark to work collaboratively on projects on their local boxes.

The Client Web Application

The web application will make up the bulk of the work for the MVP. It is responsible for rendering the text editor, including the directory tree, a menu, and one or more buffers with syntax highlighting. It will also need to handle all input, keyboard commands, and the like, and communicate with the backend. The client is actually made up of a few layers: a web server, a data layer, and a view layer. For the web server, I will use the Express package to serve the application and socket.io to communicate with the backend.

Data Handling

The data layer will store all the client-side data - that is, the state of the web application. I will apply the "single source of truth" design pattern to the data layer. In other words, all application state will live in one place, and can only be changed by making calls to that API. For a more thorough explanation, see the Redux documentation (although in fact I will be using the vues library, which is the equivalent of Redux for Vue. This approach has some advantages. It makes the application state predictable - i.e., if we know the current state, then given a series of actions we should always know what the new state will be. By keeping all state in a single place, it becomes easier to develop the rest of the application without having to worry about side effects.

View Layer

The view layer is responsible for rendering the data, and communicating user input to the rest of the client. I will use a component-based view library to implement the view layer - either React or Vue. I'm currently leaning towards Vue, because it's apparently a little more performant, but I will continue looking into them both. (EDIT 12/13/16: I've decided to use the Vue library.) Both libraries use "components" as their primary building blocks, which are modular, reusable HTML elements. Each component pulls whatever state it needs from the data store, and can pass data down to child components if they need to.

URL Handling

Spark is a browser-based app, and therefore has access to the power of URLs. All navigation within the app will have its own URL - opening a file or directory, viewing metadata, etc. Particular lines of a file will be able to be accessed using anchors in the URL. Since Spark is a single page app rather than a traditional static website, I will have to map URLs to content programatically, and I will need to be careful to match expected behavior, e.g. not breaking the back button and ensuring that the same URL always leads to the same content. I will accomplish this with the vue-router library.

There is a lot more planning work to do here, especially regarding input handling, but this suffices as a general plan.

Backend-Client Communication

As previously mentioned, the backend and the client will establish a WebSocket connection to allow bi-directional communication. There's a limit to how much detail I can plan for at this stage, but one thing I have thought about is how to communicate buffer changes. It's likely that sending input as it occurs, i.e. one character at a time, would be too bandwidth-intensive. Likewise, with that approach it would quite expensive to update the files on the backend. Instead, I will serialize input into commands, JavaScript objects that describe what the change was. This way, I can send input in larger chunks, decreasing bandwidith, and use smarter algorithms on the backend to save changes to disk. One strategy would be to keep a 'master' copy of all open files in memory on the backend, and update those buffers in response to incoming serialized actions.

Since Spark is a networked IDE, and networks go down, I plan on implementing some sort of auto-backup feature in addition to manual saving. I will handle this in a way similar to Emacs, creating copies of files currently help in memory with a .bak extension (in, say, ~/.local/spark/backups/project-name).

Janky Handwritten Architecture Notes